The Story Of Complexity

We meet the founders of the Eastern Congo-based accelerator Ensemble Pour La Difference who believe that foreign aid alone is failing to build sustainable value. By supporting entrepreneurs they want to help build an innovative business environment that addresses community needs.

Episode 1

“Social business brings value in this society, (…) because it is really touching the daily life of each one in the community.”

Patrick Byamungu

In the first episode, we meet Patrick Byamungu and Mike Beeston, both founders of the Eastern Congo-based accelerator Ensemble Pour La Difference. After working as a journalist for eight years, Patrick became tired of re-telling the same story. The story of emergency relief without lasting change. He meets Mike, who has sold his global digital agency and wants to know whether his human-centred business techniques could be relevant for entrepreneurs in the DRC. Together they start an accelerator for for-profit, social-aware businesses and tell us about the complexity of the task ahead.

Transcript

This goal brought me into contact with Patrick and Mike Beeston, Patrick and Mike set up an organization in the Eastern Congo called Ensemble Pour La Différence. I heard that they were supporting existing local business owners of small and medium enterprises (otherwise known as SMEs). They provide support and training and their overall goal is to build an infrastructure, or ecosystem, of socially aware businesses.:

I wanted to speak to them and find out how they ended up doing what they do and what they are working to achieve. Knowing a little bit about the Congo. I wanted to know how their work was different from charities and NGOs. Are they just another NGO or is there something else to learn?

I remember that the idea with Mike, I meet with Mike Beeston, at this time, I was really making many reports, video reports because I have a background and, and a solid experience in making small films and, reporting.

So I have been doing that for a long time with local NGOs. And for me, I really didn't like to continue to work in this way, because for me it was like it had become more and more like a cycle of intervention of those NGOs.

Because all the time, when we have a problem in the region, we can see the NGOs come with a strategy and start to work with people locally there. They want just to solve the emergency problem. And once the emergency problem is solved, they leave for another region and the population who stayed there - when the project is finished - the same problem comes again.

And another NGO. I don't know if it's the same, who just changed the name and come, come two years after. I don't know if they do the same, but when another NGO comes again, they come to resolve the same problem. So this really makes me uncomfortable.

I didn't realize why all, with a lot of number of NGOs who are operating in the Eastern part, why they can not think in the best way to really help people and try to build a strong society

So for me, I think this is the first big difference: this way to create wealth in the community. And this wealth, small by small, this wealth will really make a difference in the whole of the economic system of the area, where social businesses are operating.

The second difference for me: it is the habit. You know, more and more the community receives grants, the community receives donations from the NGOs. More and more, they are thinking that life is easy. They are thinking that every time when I have a problem, I will just do nothing. I will just sit and say, okay, the UN has said I need this, or another ONG (NGO), I need this. No!

So this, I think this makes the population more poor than to push them to work themselves, to try to build something themselves and to grow as social businesses.

Mike has worked in Europe, setting up global businesses in the field of design and innovation. How does his business vision apply to the small and medium-sized enterprises in Eastern Congo?

And innovation is very... I mean, the Congolese are really innovative. I mean, just as a culture, naturally so born out of need and necessity. And that can be, in a way, it can be kind of channeled or given more facilitated, you might say, with these human centered design processes in order to break through the limitations of poverty and, and some of the things like education or taxation, or, you know, historic structures which have historically kind of kept things down. Innovation can help break through those and get to the other side in a more systematic way.

Are there local Eastern Congolese who are interested in this approach? And what is the criteria that attracts La Différence?

And they're wanting to put in place proper solutions: structured, sustainable. You know, solutions that make a difference.

That’s not to say that those people who are disconnected from that don’t want to do the same thing, but how we work with, with people that distance to travel can be quite great. It can be quite a long way to bring a farmer who has never been connected, who has never been exposed to business. Who's never really understood finance, for example, that's quite a long journey to travel, to get to a successful growing SME.

So, you might say it's easy, but I would actually say it's kind of more substantial if you can work with these younger entrepreneurs, if you like, and if you can help them help the country move forward.

So you have first to prove and to have this commitment and say, okay, I want to change my life.

We are essentially working with those kind of entrepreneurs who can be able to work on this level, personal level, community level to have this view or vision to change the whole of the community.

But also our focus is not on the early stage, because the early stage, we reserve this for incubators. We know that, we have confidence that the incubators can play, very well, this role, but we are working with those entrepreneurs, or those businesses who have one or two years of experience.

Why do they need support from La Difference? What's stopping them from achieving what they want on their own?

But also, on the other hand, the social entrepreneurs are playing really a huge role because you know, there are no jobs in Congo. 84% percent of people are jobless in Congo.

Yeah. So this mass of people, what do they do every day? It is those social companies who use this mass of people every day. The government is not able to create the jobs. The job is really insufficient. The only way to go is for people to go and work in those social businesses. So the social businesses, they are really playing the role which should really be played by the government.

So, the DRC sits in Sub-Saharan Africa. Under the equator, and it is the second biggest country in Africa.

It covers an expensive land that is bigger than Spain, France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden combined. It is bordered by nine countries. It has a population of over 90 million people with almost half of them living in the cities. There are 240 identified languages with a few national ones like French, Lingala and Swahili.

The Congo is home to a wide variety of wildlife and incredible biodiversity, a huge expense of rainforest. In fact, 18% of the planet's total is in that area. And a rich supply of minerals. Tin, tantalum, tungsten, cobalt that goes into your phone and computers as well as gold, diamonds and other precious materials.

An internet search will list the DRC as both the second poorest nation in the world with a GDP of $409 per person in 2017 and almost 60 million people living on less than 1,90 a day.

But it will also show up as the richest nation on earth, with untapped deposits of raw minerals worth $24 trillion dollars. The DRC is a country whose people have known almost two centuries of rapid change, conflict and intense political instability.

From colonization to independence, to military coups, regional civil wars. And throughout this time, continuous exploitation of its natural resources by foreign countries and global corporations.

As a consequence, a staggering amount of development aid has gone into the country, more than 100 billion dollars since 1980. With the largest-ever UN presence to protect civilians and yet, the average Congolese citizen has a lower standard of living than in 1980 and the war in the early 2000s led to the death of 5.5 million people. And the insecurity continues.

This is the context in which La Difference is operating. Every day. It shows a country that has had to be resilient, and it shows the particular difficulties of building a functioning and lasting economy in the Congo.

In Patrick's lifetime, a lot has changed.

So every, every time. Congo is like decreasing. The entrepreneur sector needs, really, to work in a peaceful region. Something which is making me happy is that DRC is really going in this way.

Two years ago we succeed to change the government without war and without many trouble. So, this makes me really confident.

The difficulty comes when your savings are running low and perhaps your family and friends have provided some support, but that's running low and it's proved more difficult to establish your product or service. And, you know, you're now facing issues to do with, I don't know, the dollar Congolese Franc exchange rate, but issues that you didn't foresee are now coming in and it's a real, real struggle.

If you somehow got through this difficult phase, I think people call it the pioneer gap, and you are a success. Now you can go to investors, or lenders. But so few get through that gap. That there aren’t that many who are engaging with these, let’s say, institutional investors.

The story of La Difference is the story of people in the Congo speaking up and saying that foreign aid isn’t working. According to the World Bank, small and medium sized enterprises are essential to poverty reduction and economic growth and the International Peace Institute says they can ‘make a powerful contribution to the ecosystem of peace’. What if the future of Congo lies not with development aid, but with conscious, socially aware entrepreneurs, then the question is: what do they need to get it right?

Thanks to the help of Armant Chako, project director with La Difference, who became our journalist in the field, local entrepreneurs: Douce Namwezi, Washikala Malango and Chance Rwezi told us about their personal experience of life and setting up a social business in Eastern Congo.

And together with Patrick and Mike, they will show us how they deal with the issues of changing mindsets, ongoing corruption, leadership gaps, and how they are doing the long work of building a nurturing business environment that supports innovation.

Music Credits

Rail On - Papa Wemba // La Jolie Bebe - Docteur Nico & l’Africain Fiesta // Fabrice - Franco // Lobo Loco - Midsummer Meadow Party // Louise Marie Wa Motema - Desholey // La Vie Est Belle - Papa Wemba // Nakeyi Abidjan - Docteur Nico & l’Africain Fiesta // Mama Na Mwana - Jean Bosco Mwenda

Stepping Into Risk

Two entrepreneurs from Eastern Congo who have made a business out of their personal mission tell us how they have set about solving social problems through their enterprises. They share their motivations and successes as well as the every day challenges they face.

Episode 2

“That's what an entrepreneur does. They see a gap, they've kind of got an idea of what's on the other side of the gap and they take that step.”

Mike Beeston

In episode two, we meet entrepreneurs in Eastern Congo who have made a business out of their personal mission. From her factory in Bukavu town, Douce Namwezi and her team want to improve the position of women in their communities and have set out to address this through the production of feminine hygiene pads. But can you set up a business around a product no one feels comfortable talking about? Six hours north, in the city of Goma, Washikala Malango and his company Altech are on a mission to eradicate energy poverty. Do they have what it takes to build a nationwide business in a country where two thirds of households can’t afford the solar powered products they make?

Transcript

But first, for those of you who are entrepreneurs, you might know what it takes to begin a business. But for those of you who aren't, it is both daunting and simple. It is about taking that first step.

But where do you start? Mike, who has a history of entrepreneurship talks to me about how he sees it, and whether there are any additional challenges for entrepreneurs in the Congo.

That's what an entrepreneur does. They see a gap, they've kind of got an idea of what's on the other side of the gap, and they take that step.

You’re definitely carrying something as an entrepreneur. You're definitely carrying, um, family, community weight. But your drive is very conscious of that. But of course it has to be focused on what you're doing, why you are doing it and how to make that grow and make it sustainable. Of course, you have to put your, your heart and soul into that, but you are conscious of this, this community context more so than we are here.

You're conscious of that, but you can't get kind of dragged down too much, because it can drag you down and it can stop you. So you must, you know, you must really drive beyond it to a certain extent.

Many people are already aware that, you know, the catalyst is already in them. And I think that, in a way, the trigger to be able to do something about it is, you know, maybe a particular person that they've met or, an experience that they've had, like with Washikala.

In a way they've... it's been an aggregation of thing which has happened and allowed them in a way to step out of their, out of the general problem of Congo, which is suppression. Circumstances suppress people. But this kind of aggregation of their internal drive. Meeting or having a connection with something; an education and opportunity. They all collide together and they step into it. They intuitively say, I've got an opportunity now and I'll step forward and do something about it.

But all of them will have had that experience. But internally it was already there. Just as it is in many, many, many people, but in Congo, the opportunity is rarely there. And that's probably the catalyst.

Under her arm, a list of questions that we'd discussed. Her first stop was Douce Namwezi. Is it true for Douce that she just stepped into risk? What motivated her to get into business?

And, I was asking myself, what can we do to resolve this, this kind of situation? As a journalist, I could only give my microphone, I could only give voice to the problem, but I couldn’t act in any other way. So, with other friends we reflected on how setting up an organization that could bring another solution.

They work online and in the community, showing how to support girls and women, by on the one hand, breaking through the taboo and on the other, literally making pads available.

And there is this taboo around menstruation that makes a lot of girls lose school, first of all. And when they lose school, there is no teacher who can come back and say, I can do an exam or I can give you a test again.

And once she loses school, just because she is in her menstruation, this is not normal. Because afterwards other pupils will continue studying and she will not. Also, there are lots of consequences of not having a good menstruation education. There are a lot of girls who get pregnant only because they were not aware that they can now become pregnant.

And also there is no education among boys and men around menstruation, and most of them they think that this is dirty, or when a woman is in her menstruation, she can't cook. She can't be in front of you, or she can't be near you.

And, when it's come to participating freely in a decision-making position, for example, in politics and others, if you are a woman who became pregnant, for example, and you are called here a “mother girl”. It's not easy for you because a lot of people will point to you and will say: “She's not a good wife. She's not a good woman.” Only because she got pregnant. And when you reflect on why she got pregnant, it is just because she didn't receive education around menstruation.

So these kinds of needs, they are really important to be taken into consideration, because they influence the way women will be living in the coming years, and in the coming days.

There are these kinds of problems, these kinds of needs that are really important to be reflected on, so they can influence the future of these women. They can influence the position of these women in the future, in the community.

So for example, she has been manufacturing sanitary pads because of course sanitation, and these kinds of issues for the girls in Congo is a big issue. And she's been trying to find answers to that. And those answers have to be commercially sustainable in the long run.

But she has a wider spectrum of interest because she's been involved in journalism and women's issues for many, many years.

The DRC ranks number 183 out of a total of 190 countries. Things like dealing with construction, permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credits, paying taxes, trading across borders are all measured. And for each of these, the DRC ranks very low: somewhere between 144 and 187.

There was one such metric in which it ranked pretty high. Which was the ease of starting a business, coming in at number 54.

Reasons why this is easy or has become easier, is that the government has started simplifying procedures: creating a one-stop shop, reducing capital requirement… and from 2019 onward, the DRC no longer makes it mandatory for female entrepreneurs to get their husbands approval, to set up a business.

So what is the current position of women in the Congo?

Some of them, they are ministers. They are accessing on the ministry and also a big part of different political platforms. In our case, in the entrepreneur sector we work with a woman who decided to start a micro-hydro project. For us it was a surprise to see a woman, who is really determined and who wants to do a hydro project. So we support her and she succeeded.

But first, we're going to hear from Washikala Malongo, a social entrepreneur in Goma.

As the co-founder of the solar tech business Altech. Washikala has managed to establish a social enterprise that has 60 outlets, an access network of a thousand of sales agents, and 200 full-time equivalent employees. It distributes a range of solar-powered household products.

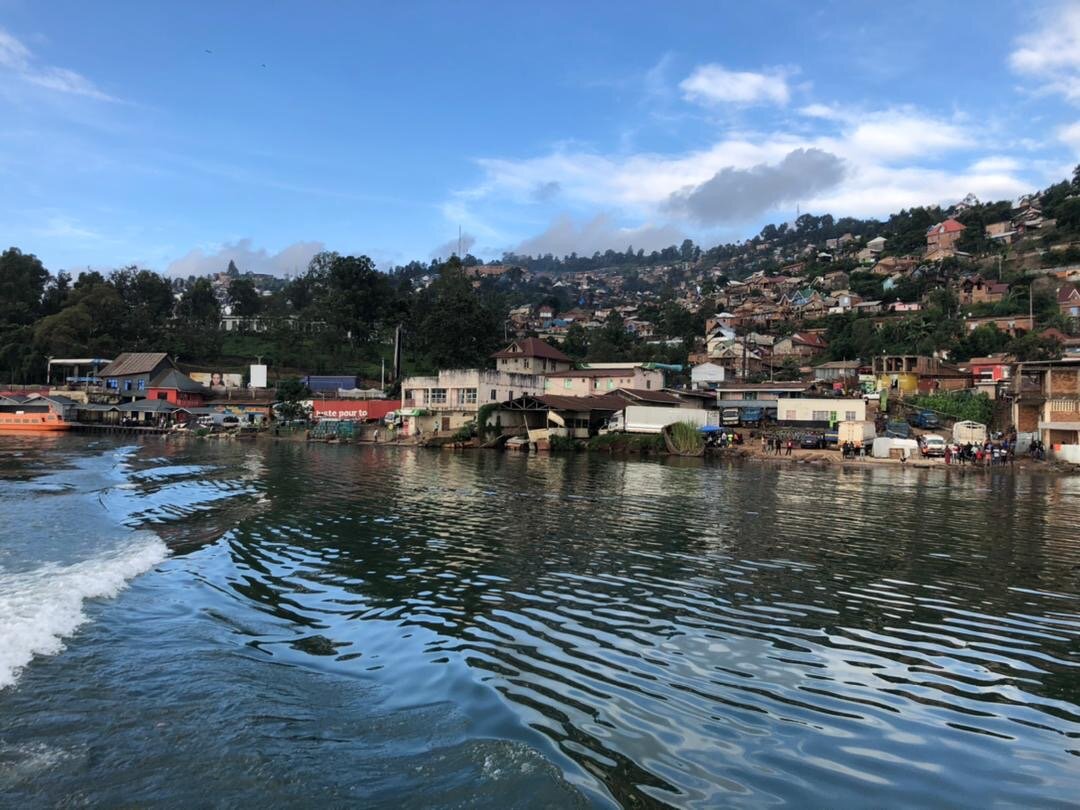

Altech company headquarters is based in Goma where Armant went to visit, taking a six-hour boat from Bukavu.

And during my stay in that camp, which was called the Nyarugusu refugee camp, I got this scholarship that took me to the university of Dar Es Salaam. And after that, after my studies at the university for Dar Es Salaam, I decided with Iongwa (co-founder) to come back to the DRC. And when we, when I arrived here, I worked a little bit with the UNHCR on some integration projects.

And then after that, I decided to found Altech group with Iongwa.

Iongo and I were both born in Eastern Congo. And we also fled to Tanzania, at the same time for safety during the Civil wars in the 1990s. And we went to the same refugee camp. And then we even also got the scholarship I talked about.

So during our studies at the University of Dar Es Salaam, we started discussing about energy poverty in the DRC, because we took a course on energy and the environment. And so, we decided to go back to the DRC and to start the company in this field. We decided to just return to Eastern Congo,and then we started Altech group and, you know, piloting the distribution of a few thousand solar lamps.

Over a decade ago in 2009, only 11% of the DRCs total population had access to electricity. 10 years later in 2019, it was 19%. So though the access rates are improving overall, they are still very low. Especially in rural areas, where about only 4% have access to electricity.

The DRCs potential to generate energy is high. Having a wide range of both renewable and non-renewable sources from hydro-power, biomass, solar, wind and geothermal, as well as fossil fuels, oil and natural gas. Approximately 9% of the country's generated domestic power comes from hydropower, specifically from two dams. The INGA dams.

During Mobutu's presidency from 1965 to 1997. The first large infrastructural project called INGA barrage was built in the Congo river. It was to provide 351 megawatts of electricity, as well as drinking water. INGA II two was completed in 1982, becoming one of the biggest water power dams in the whole of Africa providing almost five times as much electricity.

All of Mobutu's prestige projects had something in common. They were built by foreign companies, incorporated the latest technological features and were delivered as turnkey solutions. And… they never worked properly.

And the hightech would be in the hands of local people who were not trained and who didn't know how to deal with it. Moreover, turbines were built to deliver energy to national projects, with no thought being given to branching the energy out to communities along the way.

There is a lot of interest and goodwill from the international community to solve the problem of energy access and poverty. But what if these solutions started locally with people who understand the circumstances and the complications.

So they're trying to find affordable ways, ways that in a way, onboard people into the system. Cause, so many solutions in other parts of Africa, there is a level above Congo. Congo is this kind of step, it's not in the same economic circumstance, for example, as its neighbours. So you have to, in a way, kind of rebase your thinking in order to engage or to help people engage with, for example, buying a lamp.

If a solar lamp costs $30, then that's impossible for most people in Congo, they just simply can't. Even if it's $10, they can't. So, you need to find a way to help them start paying for that lamp at less than a dollar and continue paying to the end and make sure that you're, in a way, understanding of their circumstances so that they can actually finish that payment and own that lamp.

Washikala and Iongo really, really understand that, and because they understand Congolese circumstances and how to address them, they've been able to grow a business from scratch. To the point where this year, it’s budget for this year is over $8 million, which in the Congolese terms is fantastic.

And also, as I said, we also receive calls. Whenever a customer, for example can say: “Yesterday, my agent didn't come and I slept in completely darkness. Please tell him to come.”

So, they will receive the call. And also if the customer has a problem with their solar home system, they call, receive the call and then we give it to our technicians, the logistics department, so that they can follow up and make sure the customer is well served.

But again, we decided to focus on teachers and health workers. So what we're doing now was to sell - on credit - those products. To sell to teachers and health workers.

And what we realized was that the repayment rate was almost 90%. So, we were very optimistic that this is a model that would work across the DRC, and that's why we decided to start scaling it.

Then you place an order for the product you want. For now we have only one product available: the cook stove. You place an order. Then we have an Orange money and we have an Airtell money, and a Vodacom, an M-Pesa account. So after ordering you pay, you choose to pay by the carrier you want. One of the two operators, you pay. Then after you've paid, we see that the order has come, and you can receive the payment through an SMS. We see someone has paid.

And then in every city where we are, we have pickup points, where you.. Let's say in the area, we have to pick up points. If you purchase a product, you order, you pick your products from there. We make it easy for everyone around, you see, to pick a product from nearby places.

They know their environment and their customers, which is necessary to build solutions that are rooted in community needs, but they also know they need to be agile and check their assumptions.

That is, that was very important. It was one of the biggest lessons. Sometimes it is important in any type of business to learn quickly, because when you start the business, you always come up with several assumptions and sometimes when you test those assumptions, you'll find that they will not work. And some people, they keep on working on the same assumption instead of like, you know, realizing maybe these are not the best assumptions. And you should, maybe it's important to adopt a new assumption.

You can find the who cares, wins podcast on any podcasting service or visit Lilycole.com/who-cares-wins

Music Credits

Ntumba - Docteur Nico & l’Africain Fiesta // Fabrice - Franco // Leo Ni Furaha - Jean Bosco Mwenda // La Vie Est Belle - Papa Wemba // Mama Kilo - Jean Bosco Mwenda // Cherie Julie Nalingaka - Docteur Nico & l’Africain Fiesta // Kongo Nsi Eta - Mavula Baudouin

The Gift Of Trying

We start to see the bigger picture – and why these entrepreneurs feel they need to keep on trying. Despite dealing with complexity on a day-to-day basis, they are determined to work toward their greater plan.

Episode 4

“Seeing what we have achieved so far, it gives us more confidence in what we are doing and also being more ambitious than before.”

Washikala Malango

In the fourth and final episode of this series we see the bigger picture – and why these entrepreneurs feel they need to keep on trying. Despite dealing with complexity on a day-to-day basis, they are determined to work toward their greater plan. Patrick, Mike, Douce, Washikala and Chance might be on to something. By starting and supporting these businesses, they have created a new model for people in the region to take ownership of their future. What are the ingredients for long-term impact and building ecosystems that flourish? We revisit Mike and Patrick and find out whether their approach could become a model for others. Could they be getting it right?

Transcript

Last episode, we met with Douce Namwezi, Washikala Malango and Chance Rwezi, who told us about the challenges that they face. Practical institutional and cultural challenges in sectors like agriculture, clean energy and women empowerment. For this final episode, we go deeper into the strategies that they have found to deal with their challenges and where they are taking their businesses from here.

Before we hear from the others, let's go back to La Différence for a bit. Mike and Patrick have been guiding us through this story, but what exactly do they bring? What does their support look like?

That's why the team out there is fundamentally Congolese, I’m like the facilitator, the step on which they stand, right. It's not me, it's not about me. But that background that I have and other people have from Europe or wherever, that background can facilitate, it can help. It can strengthen. It can contribute to their way forward. And that's how I see what we're doing.

We want to build a model. A clear, clearly effective and sustainable model for bridging that gap. And give people confidence that it can be repeatable. And others can do it. Give people who are at the institutional side end of it, ie. the upper end of it, confidence in what we are doing so that they, by turn, have confidence in the entrepreneurs that we're helping to take that journey.

So that at the end, we have a model, which in a way is able to grow and act as that kind of missing link you might say, so that this SME sector can develop in Congo. And all around the world, there is evidence that this SME sector is a fundamental building block for a secure, stable, peaceful society.

It doesn't exist in Congo or in Eastern Congo, not really. But by building it, we can hopefully get there.

So, the entrepreneur can learn a lot of things regarding, for example, the value proposition, how to run the businesses, how to manage some risk in their businesses. So, we have a huge curriculum and programme on this.

The second value which we bring is to help them to access a financial system. Yeah, because without financial, they cannot grow. The business cannot grow. At some level, they need financial support.

And we have to connect them sometime to some potential investors, who come from outside, or sometimes also we connect them to some bank. Who can provide them a loan, or who can invest or who can buy some share in their businesses.

So essentially this is the two levels where we are supporting them.

When we began, we didn't have really good material and we always asked the consumers for their feedback of what they think and how they think we can improve.

So, we could be more open to their needs. And, we are always improving our material.

When, for example, the clients or the women and girls, they say, for example, this kind of tissue, it's not easily washable, we try always to find other tissue in cotton that can be easily washable.

And when we make a small survey and we feel people are satisfied, we are also happy. And we try to ask again and again on Maisha Pad, for example, how do you think? What topics do you think we can talk about through social media?

And we always received topics from people who are members now of this Maisha Pad community. And, because at the beginning we were the ones to decide what will be talked about. But now, when it's other people who say: “I would like during the weekly meeting, the weekly discussion that we talk about XYZ problem.” We feel that this is really, really, really good. And this is improvement in the way we are doing things.

And also, we are trying or to mix this social entrepreneurship of making and selling pads with other domains. Uwezo, we are working also in new technology of information on the communication, and we are trying to see how we can use social media and other communication tools to influence people's way of thinking, way of living, way of talking.

And through culture, cultural messages, how we can, for example, ask a comedian to perform something about menstruation and, it can make people laugh, but the message is there. And so, this kind of way of doing things, helps a lot.

He explains: “if one entrepreneur produces fish, another entrepreneur packages that fish, another produces cornmeal, or creates a hotel to accommodate people and yet another provides connection and facilitates communication through the internet. Then this complementarity will develop the village and Idjwi could become an even more attractive place than it already is today.”

But fundamentally, yes, have a group of SME successes, particularly those which are focused on these kinds of outcomes, which are social benefits, for example, in clean energy.

Where those benefits touch upon the wellbeing and sustainability of the whole community, not just this SME sector. If we can help to establish that, then that then becomes a model which is then credible, replicable, then that I think would be our job done.

But it's going to take a long time. A long, long time. You know, I mean, we just keep going. It's the right thing to do, we think. And the vision is.. it’s going to work.

When trying to build a business environment, it's about collaboration. Collaboration with other actors in the field, like government, NGOs, civil society, the church, businesses, and it's about complementarity. So using and buying local products and supporting each other.

It's another name for what attracted me to make this podcast. It refers to what some people call building an ecosystem. Patrick says it like this.

And 84% of those businesses show that they are growing. And it is something which is really good for us, is really good to know, and it continues to encourage us.

Those businesses now, they are bringing revenue and services to more than five thousand families in the region. And the products which are being produced by those businesses are really contributing a lot to the daily life of the community.

And more than a million people in Kivu are really impacting on this change. So briefly, this is the impact which we have until now.

And even if it's one or two or three women who can give her testimony and say that she feels more empowered or more happy in her body. Or, she's not any more afraid of going to school with using a piece of cloth. And that by using Maisha Pad she's feeling really happy. I'm also happy and I feel like we are good in what we are doing.

No, because we still have work. We still have a way to work on.

When I see a community like Bukavu city, it's somehow easy to approach people to talk with them about menstruation, about pad, et cetera. But when I see rural communities with all these problems related to poverty and low economic empowerment of women, then I think like there's still a lot to do.

Of course, the vision is there, it’s watching me. I feel like I have to find everyday new strategy, new ways of doing things. For me. I can't rest until the last rural Congolese woman have her pad, so I can say that it's like I achieved my vision.

We should also, I think, understand that there are several ways of addressing these problems. You know, people can get involved in politics, they can get involved in business. It can also be involved in the social sector. In most cases, what we see is like, a lot of people think that it's only through politics that they can affect change or bring about change in our country.

But, it's important that people realize that entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship, also has a big role to play in bringing change and developing our country. So, I would encourage a lot of us, a lot of young people, young Congolese, to be involved in entrepreneurship and be able to affect change.

And this social aspect will be the leitmotif of when you just want to stop because there are a lot of problems in business. You will be doing business, yes., but you'll be also changing lives of people. So, when you want to do something, just ask yourself how will I impact my community with what I'm doing.

This series on the Congo was designed to understand how entrepreneurs in the region are creating value, how they are building an ecosystem so that local businesses can flourish in the area.

Remember how we started this series? Patrick told me how uncomfortable he had become with repeating the same story over and over again. How he had wanted to influence the lives of his fellow Congolese in a way that would last.

So, I asked him at the end of our interview, if he went back to his previous work and what he does now, does he feel that he might be getting it right?

And this cooperative has more than 200 members. 200 members means 200 families. Each family has six or five children, or people who are living in the family.

Supporting these cooperatives means that you are supporting all those who are members and are family in the cooperative. So, for me, I think this is really something which I should do for the rest of my life.

↑ Write transcript above this line ↑

Music Credits

Nasalin Eloko Te - Docteur Nico & l’Africain Fiesta // La Jolie Bebe - Docteur Nico & l’Africain Fiesta // Mama Kilo - Jean Bosco Mwenda // Bukole - Bakasa Leon // Kongo Nsi Eta - Mavula Baudouin // Ekedy - Manu Dibango // Rail On - Papa Wemba