Stepping Into Risk

Episode 2

“That's what an entrepreneur does. They see a gap, they've kind of got an idea of what's on the other side of the gap and they take that step.”

Mike Beeston

In episode two, we meet entrepreneurs in Eastern Congo who have made a business out of their personal mission. From her factory in Bukavu town, Douce Namwezi and her team want to improve the position of women in their communities and have set out to address this through the production of feminine hygiene pads. But can you set up a business around a product no one feels comfortable talking about? Six hours north, in the city of Goma, Washikala Malango and his company Altech are on a mission to eradicate energy poverty. Do they have what it takes to build a nationwide business in a country where two thirds of households can’t afford the solar powered products they make?

Transcript

But first, for those of you who are entrepreneurs, you might know what it takes to begin a business. But for those of you who aren't, it is both daunting and simple. It is about taking that first step.

But where do you start? Mike, who has a history of entrepreneurship talks to me about how he sees it, and whether there are any additional challenges for entrepreneurs in the Congo.

That's what an entrepreneur does. They see a gap, they've kind of got an idea of what's on the other side of the gap, and they take that step.

You’re definitely carrying something as an entrepreneur. You're definitely carrying, um, family, community weight. But your drive is very conscious of that. But of course it has to be focused on what you're doing, why you are doing it and how to make that grow and make it sustainable. Of course, you have to put your, your heart and soul into that, but you are conscious of this, this community context more so than we are here.

You're conscious of that, but you can't get kind of dragged down too much, because it can drag you down and it can stop you. So you must, you know, you must really drive beyond it to a certain extent.

Many people are already aware that, you know, the catalyst is already in them. And I think that, in a way, the trigger to be able to do something about it is, you know, maybe a particular person that they've met or, an experience that they've had, like with Washikala.

In a way they've... it's been an aggregation of thing which has happened and allowed them in a way to step out of their, out of the general problem of Congo, which is suppression. Circumstances suppress people. But this kind of aggregation of their internal drive. Meeting or having a connection with something; an education and opportunity. They all collide together and they step into it. They intuitively say, I've got an opportunity now and I'll step forward and do something about it.

But all of them will have had that experience. But internally it was already there. Just as it is in many, many, many people, but in Congo, the opportunity is rarely there. And that's probably the catalyst.

Under her arm, a list of questions that we'd discussed. Her first stop was Douce Namwezi. Is it true for Douce that she just stepped into risk? What motivated her to get into business?

And, I was asking myself, what can we do to resolve this, this kind of situation? As a journalist, I could only give my microphone, I could only give voice to the problem, but I couldn’t act in any other way. So, with other friends we reflected on how setting up an organization that could bring another solution.

They work online and in the community, showing how to support girls and women, by on the one hand, breaking through the taboo and on the other, literally making pads available.

And there is this taboo around menstruation that makes a lot of girls lose school, first of all. And when they lose school, there is no teacher who can come back and say, I can do an exam or I can give you a test again.

And once she loses school, just because she is in her menstruation, this is not normal. Because afterwards other pupils will continue studying and she will not. Also, there are lots of consequences of not having a good menstruation education. There are a lot of girls who get pregnant only because they were not aware that they can now become pregnant.

And also there is no education among boys and men around menstruation, and most of them they think that this is dirty, or when a woman is in her menstruation, she can't cook. She can't be in front of you, or she can't be near you.

And, when it's come to participating freely in a decision-making position, for example, in politics and others, if you are a woman who became pregnant, for example, and you are called here a “mother girl”. It's not easy for you because a lot of people will point to you and will say: “She's not a good wife. She's not a good woman.” Only because she got pregnant. And when you reflect on why she got pregnant, it is just because she didn't receive education around menstruation.

So these kinds of needs, they are really important to be taken into consideration, because they influence the way women will be living in the coming years, and in the coming days.

There are these kinds of problems, these kinds of needs that are really important to be reflected on, so they can influence the future of these women. They can influence the position of these women in the future, in the community.

So for example, she has been manufacturing sanitary pads because of course sanitation, and these kinds of issues for the girls in Congo is a big issue. And she's been trying to find answers to that. And those answers have to be commercially sustainable in the long run.

But she has a wider spectrum of interest because she's been involved in journalism and women's issues for many, many years.

The DRC ranks number 183 out of a total of 190 countries. Things like dealing with construction, permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credits, paying taxes, trading across borders are all measured. And for each of these, the DRC ranks very low: somewhere between 144 and 187.

There was one such metric in which it ranked pretty high. Which was the ease of starting a business, coming in at number 54.

Reasons why this is easy or has become easier, is that the government has started simplifying procedures: creating a one-stop shop, reducing capital requirement… and from 2019 onward, the DRC no longer makes it mandatory for female entrepreneurs to get their husbands approval, to set up a business.

So what is the current position of women in the Congo?

Some of them, they are ministers. They are accessing on the ministry and also a big part of different political platforms. In our case, in the entrepreneur sector we work with a woman who decided to start a micro-hydro project. For us it was a surprise to see a woman, who is really determined and who wants to do a hydro project. So we support her and she succeeded.

But first, we're going to hear from Washikala Malongo, a social entrepreneur in Goma.

As the co-founder of the solar tech business Altech. Washikala has managed to establish a social enterprise that has 60 outlets, an access network of a thousand of sales agents, and 200 full-time equivalent employees. It distributes a range of solar-powered household products.

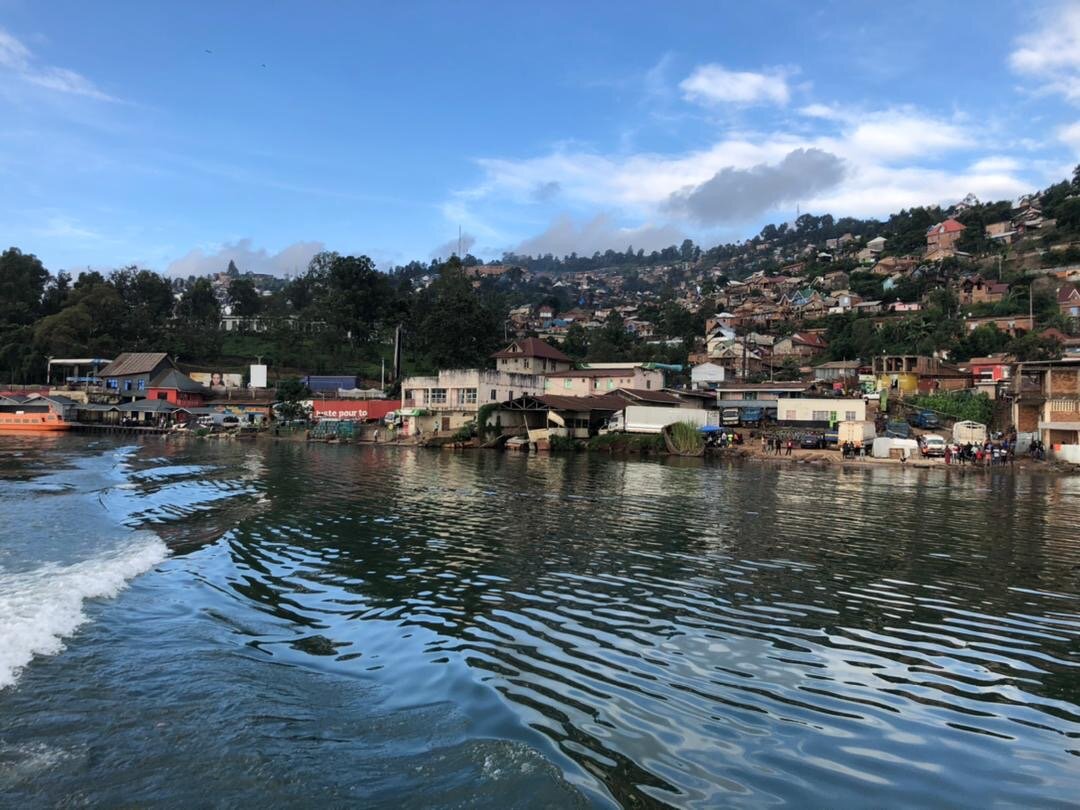

Altech company headquarters is based in Goma where Armant went to visit, taking a six-hour boat from Bukavu.

And during my stay in that camp, which was called the Nyarugusu refugee camp, I got this scholarship that took me to the university of Dar Es Salaam. And after that, after my studies at the university for Dar Es Salaam, I decided with Iongwa (co-founder) to come back to the DRC. And when we, when I arrived here, I worked a little bit with the UNHCR on some integration projects.

And then after that, I decided to found Altech group with Iongwa.

Iongo and I were both born in Eastern Congo. And we also fled to Tanzania, at the same time for safety during the Civil wars in the 1990s. And we went to the same refugee camp. And then we even also got the scholarship I talked about.

So during our studies at the University of Dar Es Salaam, we started discussing about energy poverty in the DRC, because we took a course on energy and the environment. And so, we decided to go back to the DRC and to start the company in this field. We decided to just return to Eastern Congo,and then we started Altech group and, you know, piloting the distribution of a few thousand solar lamps.

Over a decade ago in 2009, only 11% of the DRCs total population had access to electricity. 10 years later in 2019, it was 19%. So though the access rates are improving overall, they are still very low. Especially in rural areas, where about only 4% have access to electricity.

The DRCs potential to generate energy is high. Having a wide range of both renewable and non-renewable sources from hydro-power, biomass, solar, wind and geothermal, as well as fossil fuels, oil and natural gas. Approximately 9% of the country's generated domestic power comes from hydropower, specifically from two dams. The INGA dams.

During Mobutu's presidency from 1965 to 1997. The first large infrastructural project called INGA barrage was built in the Congo river. It was to provide 351 megawatts of electricity, as well as drinking water. INGA II two was completed in 1982, becoming one of the biggest water power dams in the whole of Africa providing almost five times as much electricity.

All of Mobutu's prestige projects had something in common. They were built by foreign companies, incorporated the latest technological features and were delivered as turnkey solutions. And… they never worked properly.

And the hightech would be in the hands of local people who were not trained and who didn't know how to deal with it. Moreover, turbines were built to deliver energy to national projects, with no thought being given to branching the energy out to communities along the way.

There is a lot of interest and goodwill from the international community to solve the problem of energy access and poverty. But what if these solutions started locally with people who understand the circumstances and the complications.

So they're trying to find affordable ways, ways that in a way, onboard people into the system. Cause, so many solutions in other parts of Africa, there is a level above Congo. Congo is this kind of step, it's not in the same economic circumstance, for example, as its neighbours. So you have to, in a way, kind of rebase your thinking in order to engage or to help people engage with, for example, buying a lamp.

If a solar lamp costs $30, then that's impossible for most people in Congo, they just simply can't. Even if it's $10, they can't. So, you need to find a way to help them start paying for that lamp at less than a dollar and continue paying to the end and make sure that you're, in a way, understanding of their circumstances so that they can actually finish that payment and own that lamp.

Washikala and Iongo really, really understand that, and because they understand Congolese circumstances and how to address them, they've been able to grow a business from scratch. To the point where this year, it’s budget for this year is over $8 million, which in the Congolese terms is fantastic.

And also, as I said, we also receive calls. Whenever a customer, for example can say: “Yesterday, my agent didn't come and I slept in completely darkness. Please tell him to come.”

So, they will receive the call. And also if the customer has a problem with their solar home system, they call, receive the call and then we give it to our technicians, the logistics department, so that they can follow up and make sure the customer is well served.

But again, we decided to focus on teachers and health workers. So what we're doing now was to sell - on credit - those products. To sell to teachers and health workers.

And what we realized was that the repayment rate was almost 90%. So, we were very optimistic that this is a model that would work across the DRC, and that's why we decided to start scaling it.

Then you place an order for the product you want. For now we have only one product available: the cook stove. You place an order. Then we have an Orange money and we have an Airtell money, and a Vodacom, an M-Pesa account. So after ordering you pay, you choose to pay by the carrier you want. One of the two operators, you pay. Then after you've paid, we see that the order has come, and you can receive the payment through an SMS. We see someone has paid.

And then in every city where we are, we have pickup points, where you.. Let's say in the area, we have to pick up points. If you purchase a product, you order, you pick your products from there. We make it easy for everyone around, you see, to pick a product from nearby places.

They know their environment and their customers, which is necessary to build solutions that are rooted in community needs, but they also know they need to be agile and check their assumptions.

That is, that was very important. It was one of the biggest lessons. Sometimes it is important in any type of business to learn quickly, because when you start the business, you always come up with several assumptions and sometimes when you test those assumptions, you'll find that they will not work. And some people, they keep on working on the same assumption instead of like, you know, realizing maybe these are not the best assumptions. And you should, maybe it's important to adopt a new assumption.

You can find the who cares, wins podcast on any podcasting service or visit Lilycole.com/who-cares-wins

Music Credits

Ntumba - Docteur Nico & l’Africain Fiesta // Fabrice - Franco // Leo Ni Furaha - Jean Bosco Mwenda // La Vie Est Belle - Papa Wemba // Mama Kilo - Jean Bosco Mwenda // Cherie Julie Nalingaka - Docteur Nico & l’Africain Fiesta // Kongo Nsi Eta - Mavula Baudouin